We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

7TH CIRCUIT PUZZLED BY INCONSISTENT UPWARD SENTENCING VARIANCES

Jesse Ballard was a bad boy, having compiled what his sentencing court called “probably one of the worst criminal histories I’ve seen in 30 years” of experience. From 1985 until 2017, he accrued over 30 convictions for attempted burglary, kidnapping, battery, and aggravated assault. He also committed a pile of parole violations, prison disciplinary infractions, and a few DUIs, just for good measure.

Jesse Ballard was a bad boy, having compiled what his sentencing court called “probably one of the worst criminal histories I’ve seen in 30 years” of experience. From 1985 until 2017, he accrued over 30 convictions for attempted burglary, kidnapping, battery, and aggravated assault. He also committed a pile of parole violations, prison disciplinary infractions, and a few DUIs, just for good measure.

When Jesse was sentenced for being a felon in possession of a gun (in violation of 18 USC § 922(g)(1)), the court applied the Armed Career Criminal Act’s 15-year minimum mandatory sentence as a starting point, and then – considering Jesse’s extensive criminal history – went upward from there. The judge imposed a sentence of 232 months, a 10% upward variance from the high end of Jesse’s advisory Guidelines sentencing range.

But on appeal, Jesse proved that his prior attempted burglary convictions could not count as ACCA predicates. This dropped his Guidelines range dramatically. No more ACCA 15-to-life sentencing range – now, Jesse’s statutory maximum was 10 years, and his advisory Guidelines sentencing range was a mere 33-41 months. At Jesse’s resentencing, the judge – still citing our boy’s “extensive criminal history, which it found demonstrated a disrespect for the law and an inability to live a law-abiding life” – varied upward again by 67 months, imposing a 108-month sentence.

But on appeal, Jesse proved that his prior attempted burglary convictions could not count as ACCA predicates. This dropped his Guidelines range dramatically. No more ACCA 15-to-life sentencing range – now, Jesse’s statutory maximum was 10 years, and his advisory Guidelines sentencing range was a mere 33-41 months. At Jesse’s resentencing, the judge – still citing our boy’s “extensive criminal history, which it found demonstrated a disrespect for the law and an inability to live a law-abiding life” – varied upward again by 67 months, imposing a 108-month sentence.

Naturally, this came as a shock to Jesse’s system. He headed back to the Court of Appeals. Last week, the 7th Circuit reversed Jesse’s sentence again.

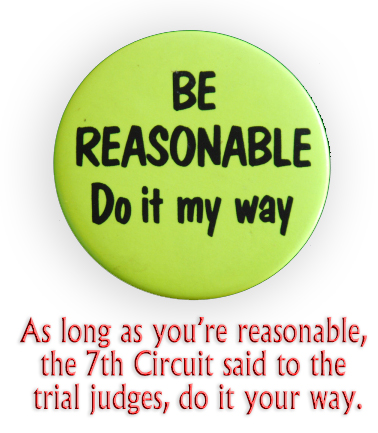

The Circuit observed that when a district court fails to adequately explain a chosen sentence, including the reason for deviation from the range, it commits a procedural error. This makes sense: an appellate court can hardly review the reasonableness of a sentence if the district court has not provided an adequate explanation for why it did what it did.

Here, the Circuit complained, the district court failed to justify the extreme difference between the second sentence’s upward variance and that of the original sentence. “To justify a sentence that was 67 months above the Guidelines range (a 160% upward departure),” the 7th held, “the court referred to… appropriate factors to consider under 18 USC § 3553. However, these were the same factors cited and discussed at the original sentencing, resulting in a sentence only 22 months above the original Guidelines range (a 10% upward departure)… The district court’s explanation of its departure from the Guidelines upon resentencing does not articulate and justify the magnitude of the variance where the explanation is essentially identical to the explanation provided for a much less extreme departure in the original sentence.”

Here, the Circuit complained, the district court failed to justify the extreme difference between the second sentence’s upward variance and that of the original sentence. “To justify a sentence that was 67 months above the Guidelines range (a 160% upward departure),” the 7th held, “the court referred to… appropriate factors to consider under 18 USC § 3553. However, these were the same factors cited and discussed at the original sentencing, resulting in a sentence only 22 months above the original Guidelines range (a 10% upward departure)… The district court’s explanation of its departure from the Guidelines upon resentencing does not articulate and justify the magnitude of the variance where the explanation is essentially identical to the explanation provided for a much less extreme departure in the original sentence.”

The district court will now get a third whack at our mischievous Jesse. This is not to say that Jesse should expect much leniency – just more explanation.

United States v. Ballard, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 4771 (7th Cir, Feb 14, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root