We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR FRIEND, HARVEY

When we were kids, we quickly learned from well-meaning parents that the policeman was our friend. That was quite true, at least up until we hit puberty or so. Then we learned, some of us later than others, that at some point the policeman has ceased being our friend, but rather was just another guy on the public dole who had been trained to believe that all “civilians” – that’s what they call us, like their Boy-Scouts-with-guns organization has anything to do with military service – are suspects and all cases have to be cleared by arrest. Arrest of the guilty party is preferred, but by no means mandatory.

When we were kids, we quickly learned from well-meaning parents that the policeman was our friend. That was quite true, at least up until we hit puberty or so. Then we learned, some of us later than others, that at some point the policeman has ceased being our friend, but rather was just another guy on the public dole who had been trained to believe that all “civilians” – that’s what they call us, like their Boy-Scouts-with-guns organization has anything to do with military service – are suspects and all cases have to be cleared by arrest. Arrest of the guilty party is preferred, but by no means mandatory.

In adulthood, we also came to realize that the prosecutor is as much our friend as is the cop, which is to say ‘not at all’? Cynical, you say? Ask the suddenly-disgraced Harvey Weinstein. Harv is clearly a guy who gives lechery a bad name, someone who used power and money to abuse women. Sure, his hormone-driven nihilism makes Bill Clinton and Donald Trump look like eunichs, and his depravity ought to earn him a one-way ticket to infamy. But that’s not enough. Word today is that the feds are investigating Harvey, a criminal-justice piling on that is as puzzling as it is troubling.

To be sure, Harvey could be convicted of multiple federal crimes. We know that for a fact, because with well over 4,000 federal criminal statutes and untold additional regulations that have been criminalized as well, anyone – from Mother Teresa to Anthony Weiner – has probably committed multiple federal crimes, often just be getting up in the morning.

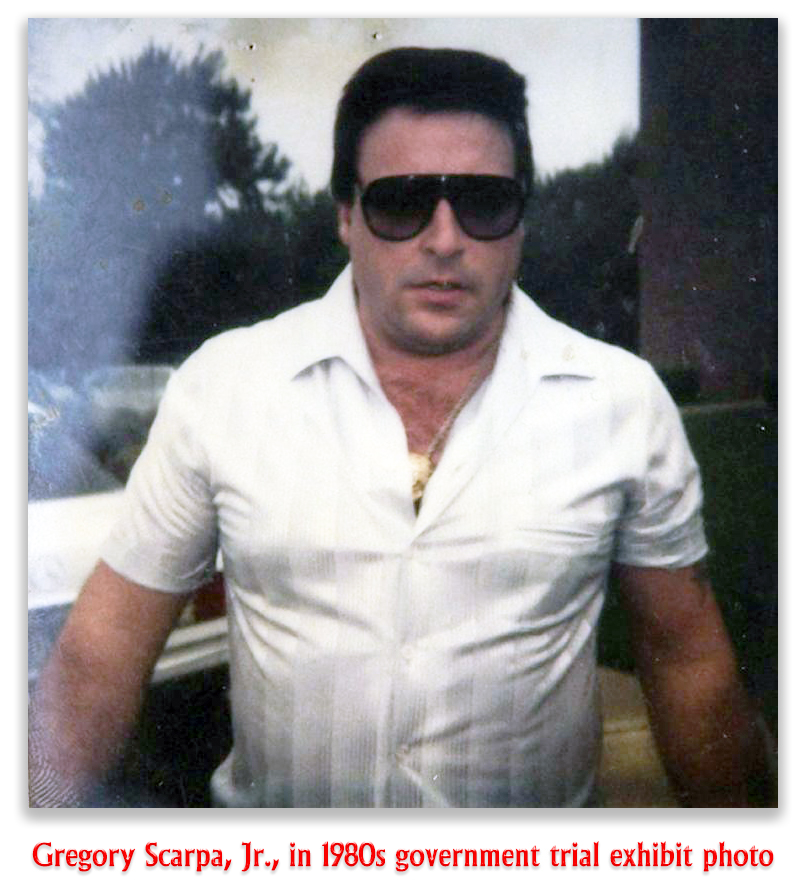

Our point to all of this is one that Aaron McMahan would appreciate. Aaron was convicted of drug trafficking in federal court, and then – like other federal inmates who come to the party late – he assisted the government in nailing a former associate. Six months after Aaron’s sentencing, his cooperation resulted in the other guy getting federal time. After that, the Government filed a post-sentence Rule 35(b) motion asking for a reduction in Aaron’s sentence as a reward for his assistance in nailing the other dude.

When defendants help the feds before sentencing, the Government rewards them by filing a motion at sentencing pursuant to 18 USC 3553(e) and Sec. 5K1.1 of the Sentencing Guidelines. This 5K1.1 motion is like a magic sentencing elixir, letting the sentencing judge ignore any advisory sentencing range, and even statutory mandatory minimums, and sentence the cooperating defendant to as little as probation.

Sometimes, however, the cooperation comes after sentencing, or – as in Aaron’s case – cooperation before sentencing has not yet brought the desired results. Then, the Government may file a motion pursuant to Rule 35(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. The Rule 35 motion is made of the same fairy dust as the 5K1.1 motion, letting the sentencing court pretty much do what it wants regardless of other statutes or guidelines.

When a defendant cooperates, no one from the U.S. Attorney’s Office promises him any reward whatsoever. Wink. Wink. This is because the defendant may be called on to testify, and the defense attorney will invariably ask him or her what has been promised. In the cross-examination pas de deux, the cooperating witness is expected to be able to respond, with rather precise honesty, that no one has promised him a thing. Of course not. Wink. Wink. Everyone knows what is really going on except for the jurors, who no doubt retire to the jury room impressed at the civic-mindedness of the felon on the stand who is willing to stand up for justice because it’s the right thing to do.

When a defendant cooperates, no one from the U.S. Attorney’s Office promises him any reward whatsoever. Wink. Wink. This is because the defendant may be called on to testify, and the defense attorney will invariably ask him or her what has been promised. In the cross-examination pas de deux, the cooperating witness is expected to be able to respond, with rather precise honesty, that no one has promised him a thing. Of course not. Wink. Wink. Everyone knows what is really going on except for the jurors, who no doubt retire to the jury room impressed at the civic-mindedness of the felon on the stand who is willing to stand up for justice because it’s the right thing to do.

Of course, after the cooperating defendant delivers, the government does not have to reward him with a 5K1.1 or Rule 35 motion, and in all but very limited cases, there is not a thing a defendant can do about it. Likewise, the court may decide not to grant a 5K1.1/Rule 35 motion, or may decide to reward the defendant with a lousy orange in his stocking instead of that pony the government recommended. In that case, a defendant’s options are pretty limited.

Practically speaking, however, the system grinds out rewards for cooperating defendants, because if it did not, word would quickly get around the jails and prisons, and cooperation would dry up.

Aaron no doubt figured that because he had delivered for the government, the U.S. Attorney was now his friend. Indeed, his “friend” delivered, filing the not-promised but reasonably-expected Rule 35 motion. Unfortunately, it seems the court was not his friend, because two days after the Rule 35 motion hit his desk, Aaron’s district judge denied the motion — before Aaron had received notice or had an opportunity to respond — explaining “even if the court were to accept as accurate all allegations of fact alleged in such motion, the court would not be persuaded that the sentence imposed on McMahan… should be reduced.”

Aaron no doubt figured that because he had delivered for the government, the U.S. Attorney was now his friend. Indeed, his “friend” delivered, filing the not-promised but reasonably-expected Rule 35 motion. Unfortunately, it seems the court was not his friend, because two days after the Rule 35 motion hit his desk, Aaron’s district judge denied the motion — before Aaron had received notice or had an opportunity to respond — explaining “even if the court were to accept as accurate all allegations of fact alleged in such motion, the court would not be persuaded that the sentence imposed on McMahan… should be reduced.”

Shocked, Aaron appealed, arguing that the district court should not have denied the Rule 35 motion without first providing him with notice and an opportunity to be heard.

Aaron was shocked again when his former friends at the U.S. Attorney’s Office argued against him in the Court of Appeals, contending that “adopting a notice and hearing requirement in Rule 35(b) motions would “create tension with the authority recognizing that a defendant possesses many more rights during the sentencing phase of criminal proceedings than during post-sentencing proceedings.”

Aaron’s dismay was complete last week, when the 5th Circuit agreed with the government. “A defendant does possess fewer rights during post-sentencing proceedings,” the Circuit held. “Indeed, Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 43(b) provides, ‘a defendant need not be present…[where t]he proceeding involves the correction or reduction of sentence under Rule 35…” Further, a defendant does not have a right to counsel during Rule 35(b) sentence reduction proceedings… Thus, a notice and hearing requirement for Rule 35(b) motions would be in conflict with Rule 43 and this Court’s previous decisions that the attendant rights of presence and counsel do not exist at that post-sentencing stage.”

Aaron’s dismay was complete last week, when the 5th Circuit agreed with the government. “A defendant does possess fewer rights during post-sentencing proceedings,” the Circuit held. “Indeed, Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 43(b) provides, ‘a defendant need not be present…[where t]he proceeding involves the correction or reduction of sentence under Rule 35…” Further, a defendant does not have a right to counsel during Rule 35(b) sentence reduction proceedings… Thus, a notice and hearing requirement for Rule 35(b) motions would be in conflict with Rule 43 and this Court’s previous decisions that the attendant rights of presence and counsel do not exist at that post-sentencing stage.”

English statesman Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, once observed that “nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.” Writ small, that is something every defendant – even someone as powerful as former Obama and Clinton buddy Harvey Weinstein – should remember about his relationship with the government.

United States v. McMahan, Case No. 16-10255 (5th Cir., October 5, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root