We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

MR. EXPLAINER TACKLES RETROACTIVE GUIDELINES

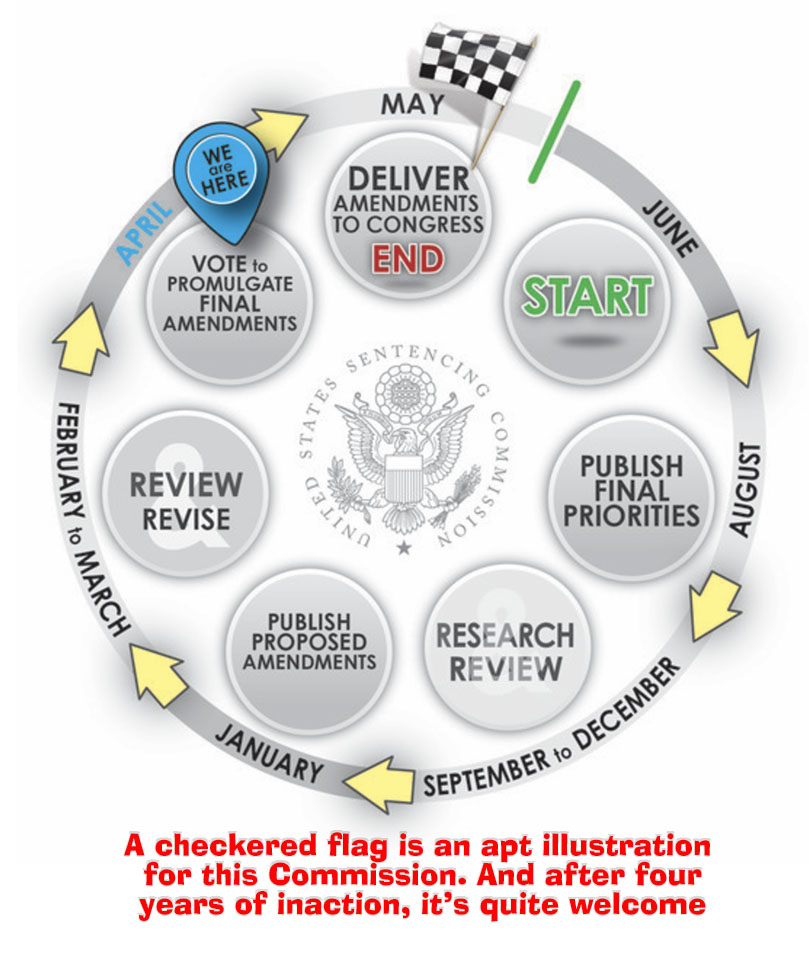

The good news is that the U.S. Sentencing Commission is likely to approve a proposal that two Guidelines changes it adopted in April should be retroactive for people already sentenced.

The good news is that the U.S. Sentencing Commission is likely to approve a proposal that two Guidelines changes it adopted in April should be retroactive for people already sentenced.

The better news is that Congress seems too busy to try to gin up a veto of any of the provisions approved by the USSC and submitted to the legislators for review.

Today’s guest is Mr. Explainer, who is here to guide us through the fine print of getting retroactive application of the two changes:

• First, no one can file a motion for retroactive application of the two Guidelines changes until six months pass from the time the USSC sends the proposed retroactivity order to Congress. That means that all of the inmates doing a happy dance in anticipation of November 1, 2023, will have to wait at least until Punxatawny Phil sees his shadow.

• Second, the two changes have conditions attached:

(a) The zero-point change in the Guidelines (new USSG § 4C1.1) says that defendants are eligible for a 2-level reduction in their Total Offense Level (usually good for a two-sentencing range reduction) if they had zero criminal history points and meet all of the following conditions:

(1) had no adjustment under § 3A1.4 (Terrorism);

(2) did not use violence or credible threats of violence in connection with the offense;

(3) the offense did not result in death or serious bodily injury;

(4) the offense is not a sex offense;

(5) the defendant did not personally cause substantial financial hardship;

(6) no gun was involved in connection with the offense;

(7) the offense did not involve individual rights under § 2H1.1;

(8) had no adjustment under § 3A1.1 for a hate crime or vulnerable victim or § 3A1.5 for a serious human rights offense; and

(9) had no adjustment under § 3B1.1 for role in the offense and was not engaged in a 21 USC § 848 continuing criminal enterprise.

(b) The change in § 4A1.1(e) – the so-called status point enhancement – says only that one point is added if the defendant already has 7 or more criminal history points and “committed any part of the instant offense (i.e., any relevant conduct) while under any criminal justice sentence, including probation, parole, supervised release, imprisonment, work release, or escape status.”

• The USSC staff has figured that about 11,500 BOP prisoners with status points would have a lower guideline range under a retroactive § 4A1.1(e). The current average sentence for that group is 120 months and would probably fall by an average of 14 months.

• The USSC staff has figured that about 11,500 BOP prisoners with status points would have a lower guideline range under a retroactive § 4A1.1(e). The current average sentence for that group is 120 months and would probably fall by an average of 14 months.

• About 7,300 eligible prisoners with zero criminal history points would be eligible for a lower guideline range if the zero-point amendment becomes retroactive. The current average sentence of 85 months could fall to an average of 70 months.

• The reduction – done under 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) – is a two-step process described in USSC § 1B1.10.

(a) First, the court determines whether the prisoner is eligible. For a zero-point reduction, the court would have to find that the prisoner (1) had no criminal history points; (2) had none of the other enhancements in his case or guns or sex charges, or threats of violence or leader/organizer enhancements or any of the other factors listed in § 4C1.1. Then, the court would have to find that granting the two-level reduction would result in a sentencing range with a bottom number lower than his or her current sentence.

If your guidelines were 97-121 months, but the court varied downward to 78 months for any reason other than cooperation, you would not be eligible because reducing your points by two levels would put you in a 78-97 month range, and you are already at the bottom of that range. Special rules apply if you got a § 5K1.1 reduction for cooperation, but people sentenced under their sentencing ranges for reasons other than cooperation may not be eligible.

(b) To benefit from the status point reduction, the decrease in criminal history points is more problematic. If you have 4, 5, or 6 criminal history points, you are in Criminal History Category III. If two of those points are status points, they would disappear. Going from 5 points to 3 or 4 points to 2 would drop you into Criminal History Category II. If your prior sentencing range had been 70-87 months, your new range would be 68-78 months, and you would be eligible.

But if you had 6 criminal history points, you would only drop to 4 points, and you would still be in Criminal History Category III. No reduction in criminal history, no decrease in sentencing range, and thus no eligibility.

• Once you’re found to be eligible, your judge has just about total discretion whether to give you all of the reduction you’re entitled to, some of it, or none of it. You cannot get more than the bottom of your amended sentencing range, and the court cannot consider any other issues in your sentence than the retroactive adjustment.

Convincing the court that you should get the full benefit of your reduction is best done with letters of support from the community, a good discipline record and a history of successful programming. Showing the court that you have been rehabilitated to the point that the reduction has been earned is a good idea.

Convincing the court that you should get the full benefit of your reduction is best done with letters of support from the community, a good discipline record and a history of successful programming. Showing the court that you have been rehabilitated to the point that the reduction has been earned is a good idea.

There’s a good reason that the retroactivity – if it is adopted – will end up benefitting no more than 12% of the BOP population. It is not easy to show eligibility and even tougher to prove that the court should use its discretion to give you the credit.

USSC, Retroactivity Impact Analysis of Parts A and B of the 2023 Criminal History Amendment (May 15, 2023)

USSC, Sentencing Guidelines for United States Courts (May 3, 2023)

USSC § 1B1.10, Reduction in Term of Imprisonment as a Result of Amended Guideline Range (Policy Statement)

– Thomas L. Root