We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

JONESING FOR SOME UNDERSTANDING

Back in 1970, Second Circuit Judge Henry J. Friendly titled his proposal for a unitary approach to collateral attack “Is Innocence Irrelevant? Collateral Attack on Criminal Judgments.” We got the answer yesterday: Yes, it is.

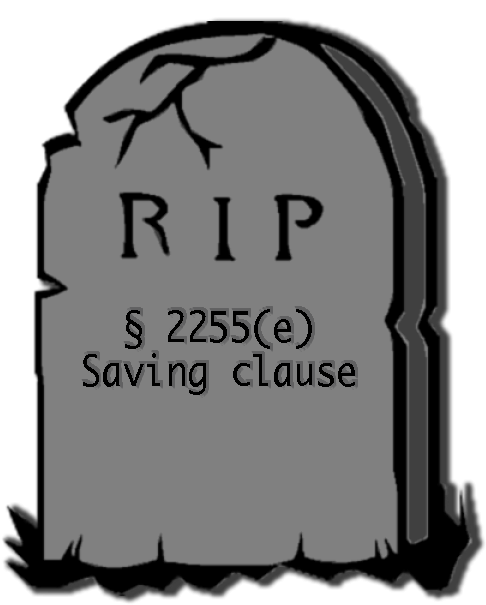

The response has been fast and furious to the Supreme Court decision in Jones v. Hendrix, which held that federal prisoners may not rely on the saving clause in 28 USC § 2255(e) to avail themselves of a Supreme Court decision that the statute under which they were convicted was wrongly applied by the trial court.

Jones v. Hendrix held that a prisoner who has done 27 years for being a felon in possession of a gun (28 USC § 922(g)(1)) could not bring a habeas corpus action alleging he was innocent of the conviction because the Supreme Court had redefined § 922(g) in the 2019 Rehaif v. United States decision to require that a defendant know that he was prohibited from possessing a gun.

Hendrix held that petitioner Marcus Jones could not file such a petition, leaving him without recourse. In so holding, the decision drives a stake through the heart of 28 USC § 2255(e).

Subsection 2255(e), known as the saving clause, provides that

An application for a writ of habeas corpus in behalf of a prisoner who is authorized to apply for relief by motion pursuant to this section, shall not be entertained if it appears that the applicant has failed to apply for relief, by motion, to the court which sentenced him, or that such court has denied him relief, unless it also appears that the remedy by motion is inadequate or ineffective to test the legality of his detention.

Before yesterday, most courts accepted that where a change in statutory interpretation made federal prisoners actually innocent of the offense of which they had been convicted, they could resort to the classic habeas corpus petition (28 USC § 2241). That was because unless they were that magic one-year period after conviction during which they could file a 28 USC § 2255 motion, a reinterpretation of a statute – rather than a constitutional holding – did not open up their time period in which to bring a § 2255 motion.

The Supreme Court sanctioned such as procedure in 1998’s Bousley v United States ruling. After the Supreme Court ruled in Bailey v. United States that 18 USC § 924(c) prohibiting the use of a firearm in drug and violent offenses meant more than mere possession of the gun, many people convicted of § 924(c) offenses, perhaps because they had been selling pot at the schoolyard but had a .22 rifle in the closet at home, were suddenly no longer guilty of the crime for which they were doing time. But because Bailey just reinterpreted § 924(c) without finding the prior interpretation unconstitutional, the prisoners were precluded from bringing a 28 USC § 2255 to challenge their convictions.

The Supreme Court sanctioned such as procedure in 1998’s Bousley v United States ruling. After the Supreme Court ruled in Bailey v. United States that 18 USC § 924(c) prohibiting the use of a firearm in drug and violent offenses meant more than mere possession of the gun, many people convicted of § 924(c) offenses, perhaps because they had been selling pot at the schoolyard but had a .22 rifle in the closet at home, were suddenly no longer guilty of the crime for which they were doing time. But because Bailey just reinterpreted § 924(c) without finding the prior interpretation unconstitutional, the prisoners were precluded from bringing a 28 USC § 2255 to challenge their convictions.

Most federal appeals courts permitted prisoners convicted under the broader interpretation of § 924(c) to challenge their convictions even if they’d previously filed a § 2255 or were beyond the original deadline. In Bousley, the Supremes sanctioned that approach provided that a change in statutory interpretation since a § 2255 motion was due to be filed made a defendant actually innocent of the offense.

The saving clause procedure permitted by Bousley was so settled that the Solicitor General refused to defend the position that petitioner Marcus Jones was precluded from raising his actual innocence of a gun possession charge under the saving clause. Instead, the Government argued for a slightly stricter showing a defendant would have to make in order to use a § 2241 petition under the saving clause.

The Supreme Court had to appoint a law firm to argue Warden Hendrix’s position. That firm, New York white-shoe firm Sullivan and Cromwell, took a victory lap yesterday, leading Above the Law to observe

It’s a sad day that someone will spend 20+ years in prison for a conviction that never actually existed… I should clarify. This has been a sad day for some. It’s not stopping the attorneys over at Sullivan & Cromwell, the firm appointed by the Court to argue that Jones shouldn’t have a second habeas petition no matter what, from rubbing the victory in everyone’s faces over on Twitter.

To be sure, not everyone was depressed over yesterday’s decision. Crime & Consequences called Jones v. Hendrix a “major victory for finality of judgments,” arguing that in the decision, “[t]he Court rejected an attempt by the petitioner to do ‘an end-run around AEDPA,’ i.e., the limits o n collateral review of convictions enacted by Congress in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996…. Even more important, the Court has finally rejected the notion that the Suspension Clause of the Constitution requires collateral review of final judgments by courts of general jurisdiction. That clause is limited to the scope of habeas corpus understood at the time, which did not include such review. Congress may authorize such review, of course, but it is fully capable of imposing such limits as deems to be good policy.”

n collateral review of convictions enacted by Congress in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996…. Even more important, the Court has finally rejected the notion that the Suspension Clause of the Constitution requires collateral review of final judgments by courts of general jurisdiction. That clause is limited to the scope of habeas corpus understood at the time, which did not include such review. Congress may authorize such review, of course, but it is fully capable of imposing such limits as deems to be good policy.”

Most of the commentary was negative, however. Vox complained

in [Justice] Thomas’s telling, the main purpose of this “inadequate or ineffective” provision is to protect prisoners who are unable to bring a habeas challenge in the court where they were originally convicted — such as if Congress later passed a law eliminating that court. Indeed, in a footnote, Thomas suggests that the “inadequate or ineffective” provision may largely be a relic of an age before the federal interstate highway system was built, when transporting a prisoner to the judicial district where they were convicted “posed difficulties daunting enough to make a § 2255 proceeding practically unavailable.”

Under Jones v. Hendrix, a “prisoner who is actually innocent, imprisoned for conduct that Congress did not criminalize, is forever barred … from raising that claim, merely because he previously sought postconviction relief,” Justices Sotomayor and Kagan wrote in a two-page dissent. “It does not matter that an intervening decision of this Court confirms his innocence. By challenging his conviction once before, he forfeited his freedom.”

The franchise dissent, however, in Jones belonged to Justice Jackson. In addition to what I noted yesterday, she observed that the majority’s approach sanctions dramatically different treatment of prisoners with virtually identical habeas claims:

Consider two individuals who have been convicted of the same federal crime—perhaps two codefendants who were tried and sentenced together. Both complete their direct appeals, but only one files a § 2255 motion within AEDPA’s statute of limitations, while the other one decides not to or misses the deadline. If § 2255(h) bars a successive petition raising a legal innocence claim, then when Rehaif is handed down—altering the elements of the crime of conviction such that both prisoners have a colorable claim of legal innocence—only the one who did not previously file a § 2255 petition can raise this retroactive statutory innocence claim.

Writing in Reason, George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin suggested that the very act of keeping a legally innocent person in prison violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment: “The clause bars the government from depriving a person of ‘life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.’ Keeping a man in prison when the activity he was convicted of was not actually illegal seems an obvious deprivation of ‘liberty’ without any basis in ‘law.’ And, because Jones never had a chance to raise the relevant issue, this practice can’t be justified on the basis of efficiency or procedural finality.”

University of Michigan law professor Leah Litman argues in Slate that “as a result of this opinion, people with illegal convictions and sentences—people who are legally innocent—will be stuck in prison for no good reason because the courts screwed up, not because they did. The law certainly did not require this result. And the Jones debacle carries a few warnings about the nightmare at One First Street. One is that the Jones majority is part of a larger trend of the Supreme Court believing that the court (and all federal courts) are above reproach and can do no wrong…”

University of Michigan law professor Leah Litman argues in Slate that “as a result of this opinion, people with illegal convictions and sentences—people who are legally innocent—will be stuck in prison for no good reason because the courts screwed up, not because they did. The law certainly did not require this result. And the Jones debacle carries a few warnings about the nightmare at One First Street. One is that the Jones majority is part of a larger trend of the Supreme Court believing that the court (and all federal courts) are above reproach and can do no wrong…”

Something that has not been pointed out yet is how Jones v. Hendrix may energize the compassionate release business. The Sentencing Commission has proposed adding USSG 1B1.13(a)(6), which holds that non-retroactive changes in the law may be “considered in determining whether the defendant presents an extraordinary and compelling reason, but only where such change would produce a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence likely to be imposed at the time the motion is filed, and after full consideration of the defendant’s individualized circumstances.”

It would be hard to imagine a disparity grosser than doing time for an offense of which one was innocent.

Above the Law, Sullcrom Is Super Proud Of Themselves For Making It Easier For The State To Confine The Innocent (June 22, 2023)

Crime & Consequences, Major Victory for Finality of Judgments (June 22, 2023)

Vox,The Supreme Court’s latest opinion means innocent people must remain in prison (June 22, 2023)

Washington Post, Supreme Court denies prisoner second chance to show innocence (June 22, 2023)

Reason, A Troubling Supreme Court Habeas Decision (June 22, 2023)

Slate, Clarence Thomas’ Latest Criminal Justice Ruling Is an Outright Tragedy (June 22, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root