We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

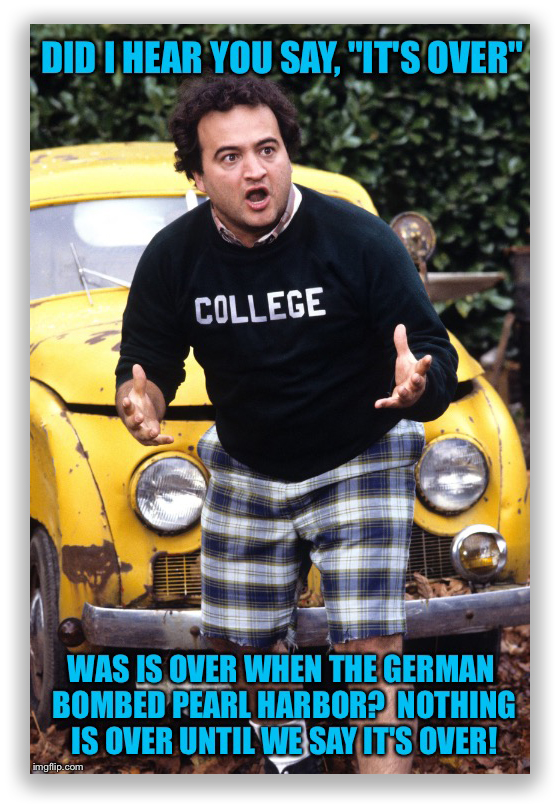

WHAT’S DONE IS DONE

If there is an enduring myth among inmates seeking to get convictions and sentences set aside, it is the canard that questions about the court’s jurisdiction can be raised at any time. We can’t count the number of times we have tried to explain that “at any time” does not mean that a defendant can waltz into court a decade after the fact to claim that the court never should have heard the criminal case to begin with.

If there is an enduring myth among inmates seeking to get convictions and sentences set aside, it is the canard that questions about the court’s jurisdiction can be raised at any time. We can’t count the number of times we have tried to explain that “at any time” does not mean that a defendant can waltz into court a decade after the fact to claim that the court never should have heard the criminal case to begin with.

To be sure, a court has a continuing obligation to satisfy itself that it has subject-matter jurisdiction, but as Jorge Mercado-Flores discovered, that obligation only lasts as long as the case goes on. There always comes a time when a criminal judgment is final, and – to paraphrase the Supreme Court – finality is a virtue.

Jorge, who is 28, was charged in Puerto Rico with a rather unpleasant offense after getting a little frisky at the beach with his 14-year old girlfriend. The government did not think Jorge’s transgression merited the 10-year mandatory minimum sentence the offense as charged required, so it proposed a plea deal in which he would plead to a different statute which carried no mandatory minimum sentence.

This was the catch. The statute Jorge was charged with criminalized “the transportation of a minor within a United States ‘commonwealth, territory or possession’.” The statute he pled to under the plea deal criminalized the transportation of an individual “in interstate or foreign commerce, or in any Territory or Possession of the United States.”

As the French say, “viva la difference!” The parties did not catch the problem, but at sentencing the district court voiced its concern. Puerto Rico is not a territory or possession, but rather is a commonwealth, in fact, one of only two commonwealths in the United States. The statute Jorge was charged under mentioned territories, possessions and commonwealths. The statute he pled to omitted “commonwealths” altogether.

As the French say, “viva la difference!” The parties did not catch the problem, but at sentencing the district court voiced its concern. Puerto Rico is not a territory or possession, but rather is a commonwealth, in fact, one of only two commonwealths in the United States. The statute Jorge was charged under mentioned territories, possessions and commonwealths. The statute he pled to omitted “commonwealths” altogether.

The district court tried to cut the baby in half. It said it would sentence Jorge, but reserve judgment on whether it had subject-matter jurisdiction to sentence him. So it did, giving him 57 months. About 24 days later, the court – acting sua sponte – ruled that it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction over the statute Jorge pled to, and dismissed the whole she-bang.

Great news for Jorge, right? Wrong. The government appealed, demanding that the district court’s decision on jurisdiction be vacated. The government said that if the appeal failed, it would reindict him under the old statute. That would expose Jorge to a minimum 120-month sentence. Jorge then filed a responsive brief with the appeals court, supporting the government’s demand that the district court’s jurisdiction decision be vacated.

Last Friday, the 1st Circuit made everyone happy, throwing out the district court dismissal and reinstating the 57-month sentence. The Circuit made it clear:

We begin with bedrock. Subject to only a handful of narrowly circumscribed exceptions, a district court has no jurisdiction to vacate, alter, or revise a sentence previously imposed… When — as in this case — a judgment of conviction is entered upon imposition of a sentence, that sentence is a final judgment and, therefore, may only be modified by the sentencing court in certain limited circumstances. Because a district court (apart from collateral proceedings such as habeas corpus or coram nobis) has no inherent power to modify a sentence after it has been imposed, those limited circumstances “stem[] solely from . . . positive law.

The appellate court reviewed the limited circumstances – a habeas corpus proceeding, a government motion to reduce sentence for substantial assistance, a motion under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) when the Sentencing Commission has retroactively lowered the guidelines. None of the limited circumstances applied here.

The Circuit complained that “the district court did not identify the source of its perceived authority to vacate the defendant’s sentence. After examining all the potential sources, we conclude that, in the circumstances of this case, no provision of positive law empowers a district court to vacate a sentence, sua sponte, more than three weeks after imposing it.”

The Circuit complained that “the district court did not identify the source of its perceived authority to vacate the defendant’s sentence. After examining all the potential sources, we conclude that, in the circumstances of this case, no provision of positive law empowers a district court to vacate a sentence, sua sponte, more than three weeks after imposing it.”

You see, “final” is “final.” The judiciary has “historic respect for the finality of the judgment of a committing court,” which “would become a distant memory” if district courts could recall their sentences whenever they wanted to, or whenever a defendant wanted to argue about jurisdiction. The 1st said, “if the criminal justice system is to function appropriately, the imposition of a sentence must carry with it an ‘expectation of finality and tranquility’ for the defendant, the government, and the public.”

The error was a simple one. The district court already had imposed a sentence, more than three weeks had elapsed, and the defendant had not sought either to withdraw his guilty plea or to vacate the imposed sentence. Given those facts, the appellate court said, “the district court was not at liberty, sua sponte, to annul the sentence. Having accepted the defendant’s plea, conducted a full sentencing hearing, and imposed a sentence, the court lost any jurisdiction to change its mind.”

Even if it lacked subject-matter jurisdiction to begin with?

Yup. Even though.

United States v. Mercado-Flores, Case No. 15-1859 (1st Cir., Sept. 22, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

Floyd was convicted of kidnapping and beating a man. After hewas convicted, the victim recanted his testimony identifying Floyd as his assailant. Floyd filed a 28 USC § 2255 motion claiming ineffective assistance of counsel at trial, denial of his due process rights (based on the recantation) and a claim that his 18 USC § 924(c) use-of-a-gun conviction should be thrown out, based on Johnson v. United States.

Floyd was convicted of kidnapping and beating a man. After hewas convicted, the victim recanted his testimony identifying Floyd as his assailant. Floyd filed a 28 USC § 2255 motion claiming ineffective assistance of counsel at trial, denial of his due process rights (based on the recantation) and a claim that his 18 USC § 924(c) use-of-a-gun conviction should be thrown out, based on Johnson v. United States.