We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BUYER’S REMORSE

With 97% of federal defendants entering guilty pleas, you’d think that law students aspiring to federal criminal defense work (that is, if any law student actually selects that as a career option) would take classes in plea negotiation even before studying evidence, criminal procedure or appellate advocacy.

To be sure, plea agreement negotiation is an art form, sort of akin to detailed choreography that has great implications for defendants, implications often never fully appreciated until much later. The change-of-plea hearing itself is a pas-de-deux for defendant and judge, with almost every question being scripted by Rule 11(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure – and almost every answer being a trap for the unwary.

To be sure, plea agreement negotiation is an art form, sort of akin to detailed choreography that has great implications for defendants, implications often never fully appreciated until much later. The change-of-plea hearing itself is a pas-de-deux for defendant and judge, with almost every question being scripted by Rule 11(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure – and almost every answer being a trap for the unwary.

It’s little wonder the Supreme Court has held that the 6th Amendment’s right to effective legal counsel extends to negotiating and signing the plea agreement.

Gilbert Spiller was a man without a lot of choices. He was busted in Chicago for selling 121 grams of crack to a police informant, and then compounding his miscalculation by later selling the same guy a loaded .40 caliber pistol so the buyer – a convicted felon – could use it to protect his own drug trafficking operation. Gil was sort of a poster boy for what’s wrong with the Windy City.

Gil, a man with three prior drug felonies, was pretty much in a corner. The federal drug trafficking statute – 21 USC 841 – is a spaghetti bowl of “if-thens.” If the amount of drugs sold exceed x, then the minimum sentence becomes y. If the defendant has x number of prior drug felonies, then the minimum sentence is y, but if the number of prior felonies is x+1, then the minimum sentence is 2y. If death or serious injury resulted from the drug sales, then the minimum sentence is z. In Gil’s case, the amount of drugs he sold would have given him a mandatory minimum sentence of five years, but his prior felonies bumped it to double that.

When the government intends to enhance a 21 USC 841 sentence, it has to provide a notice complying with 21 USC 851. In defendant parlance, someone receiving such an enhanced sentence has been “851’d.” Gil got 851’d right away, even before the government’s plea offer arrived on his lawyer’s email.

When the government intends to enhance a 21 USC 841 sentence, it has to provide a notice complying with 21 USC 851. In defendant parlance, someone receiving such an enhanced sentence has been “851’d.” Gil got 851’d right away, even before the government’s plea offer arrived on his lawyer’s email.

The government proposed that Gil would plead to a drug distribution count, and admit that the conduct underlying the remaining counts was relevant for sentencing purposes. He also had to stipulate to the government’s Guidelines calculation, including a Guidelines “career offender” enhancement that would send the sentencing range into the stratosphere.

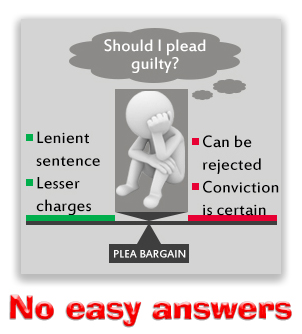

Gil’s defense attorney was puzzled by the offer. Gil would be giving up his right to appeal or argue Guidelines enhancements at sentencing, and for what? We see this in many plea agreements: the defendant give up rights in exchange for vapor, getting nothing that he could not have gotten simply by pleading guilty without the agreement (called a “blind plea”). After all, a defendant does not have to have an agreement in order to plead guilty, and sometimes, no plea agreement might be a wise idea.

Gil clearly wondered what was in the deal for him, as did his attorney. She wrote back:

Mr. Spiller has asked a great question and one that I cannot seem to answer for him: what exactly does he gain if he proceeds by plea agreement, as opposed to a blind plea. Is the government withdrawing the 851? Can you tell me one concession the government makes in the draft plea you sent over? I want to make sure I am not missing something.

In an uncharacteristic flash of candor, the Assistant U.S. Attorney responded:

The government is not withdrawing the 851 notice. You ask a good question, and I admit that the plea agreement does not offer a whole lot beyond a blind plea. There are a few minor benefits: we would dismiss two counts so he would save himself $200 in special assessments. He also gets the recognition in the plea agreement that, as things currently stand, he is entitled to acceptance of responsibility.

Gil rejected the government’s proposed plea agreement and instead entered a blind plea, pleading guilty to all three counts and reserving his right to argue his sentence and appeal. His sentencing range was 262-327 months. At sentencing, his lawyer pointed to his troubled upbringing, asking for 120 months. The court sentenced Gil to 240 months.

Gil rejected the government’s proposed plea agreement and instead entered a blind plea, pleading guilty to all three counts and reserving his right to argue his sentence and appeal. His sentencing range was 262-327 months. At sentencing, his lawyer pointed to his troubled upbringing, asking for 120 months. The court sentenced Gil to 240 months.

Once ensconced in prison, Gil became afflicted with buyer’s remorse. He filed a 28 USC 2255 motion, arguing his lawyer had been constitutionally ineffective by counseling him to execute a blind plea rather than taking the government’s proposed plea agreement. The district court denied the motion.

Last week, the 7th Circuit upheld the denial. To win, Gil had to show his lawyer’s performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness, and that there was a reasonable chance that, but for those errors, his sentence would have been different.

The Circuit said that a reasonably competent lawyer would have tried to learn all of the relevant facts of the case, make an estimate of a likely sentence, and communicate the results of that analysis to the client before allowing him to plead guilty. That, the Court said, was just what Gil’s lawyer did. She discussed the proposed plea agreement with him and conveyed Gil’s questions (and hers) to the government. She concluded that Gil would be better off rejecting the offer and pleading blindly.

In fact, she went one better that most attorneys. She drafted an 11-page plea declaration illustrating the understanding of the relevant facts and law underlying the case that she and Gil had reached, which she had Gil sign. In the document, which was filed with the district court, Gil acknowledged he had read the indictment and the document he was signing, and had gone over the whole thing with his attorney. (This, in our experience, is an unusual but prudent practice: it both ensures the defendant knows what is happening and protects the lawyer from “buyer’s remorse” proceedings such as Gil’s 2255 motion).

In fact, she went one better that most attorneys. She drafted an 11-page plea declaration illustrating the understanding of the relevant facts and law underlying the case that she and Gil had reached, which she had Gil sign. In the document, which was filed with the district court, Gil acknowledged he had read the indictment and the document he was signing, and had gone over the whole thing with his attorney. (This, in our experience, is an unusual but prudent practice: it both ensures the defendant knows what is happening and protects the lawyer from “buyer’s remorse” proceedings such as Gil’s 2255 motion).

Gil admitted in his 2255 motion that his attorney believed it was worth it to reserve his right to challenge the government’s Guidelines calculation — a right he would have sacrificed by signing the plea agreement — and believed she could get him a “better sentence.” The Court said her decision “sounds in strategy rather than in emotion, and a strategic decision, even if clearly wrong in retrospect, cannot sup-port a claim that counsel’s conduct was deficient.”

The Circuit observed that a “fair assessment of attorney performance requires that every effort be made to eliminate the distorting effects of hindsight, to re-construct the circumstances of counsel’s challenged conduct, and to evaluate the conduct from counsel’s perspective at the time.” This is especially true in the plea-bargaining context, the Court said, citing “the many uncertain-ties surrounding the difficult decision of whether to plead guilty.”

The Circuit observed that a “fair assessment of attorney performance requires that every effort be made to eliminate the distorting effects of hindsight, to re-construct the circumstances of counsel’s challenged conduct, and to evaluate the conduct from counsel’s perspective at the time.” This is especially true in the plea-bargaining context, the Court said, citing “the many uncertain-ties surrounding the difficult decision of whether to plead guilty.”

The 7th concluded that the district court had “a sufficient basis in the record to characterize counsel’s decision as strategic: Her email, Spiller’s affidavit, the government’s proposed plea agreement, and Spiller’s Plea Declaration, taken together, obviated the need for an evidentiary hearing.”

Spiller v. United States, Case No. 15-2889 (7th Cir., Apr. 28, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root