We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BOP SMACKED BY CHEVRON BUT STANDS TOUGH ON DENYING FSA BENEFIT

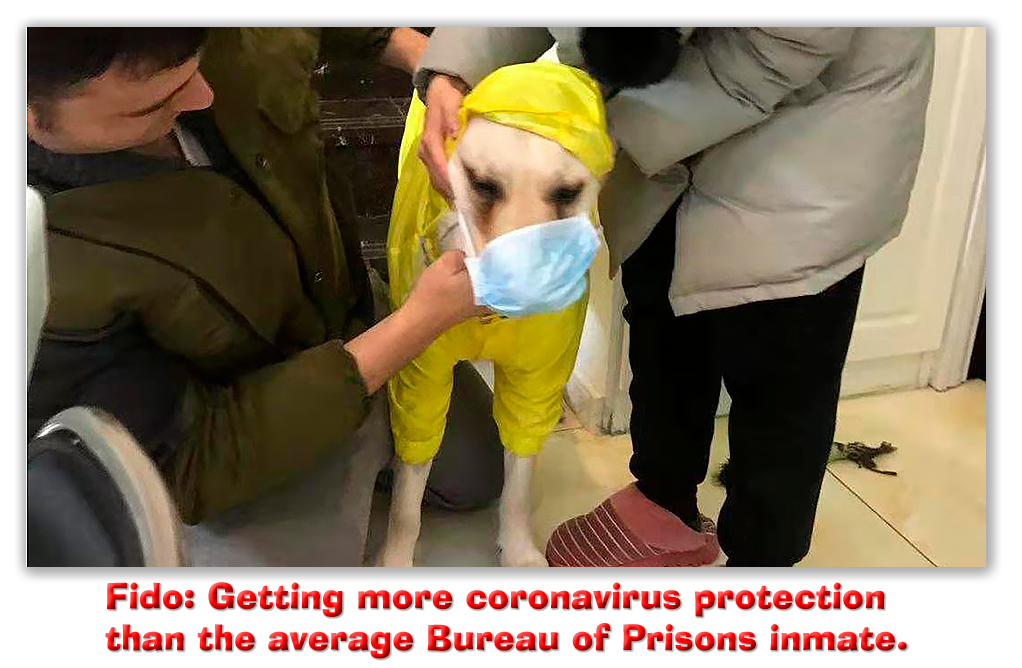

Writing in Forbes last week, Walter Pavlo flagged a First Step Act credit benefit that the Bureau of Prisons has been denying to prisoners except where courts order otherwise. With the Supreme Court primed this term to rein in the Chevron deference doctrine – the judicial rule that courts defer to federal agencies’ interpretation of the statutes they administer – the BOP’s denial of FSA credits until an inmate reaches his or her assigned institution is an excellent case of how even Chevron can ban some BOP overreaching.

Writing in Forbes last week, Walter Pavlo flagged a First Step Act credit benefit that the Bureau of Prisons has been denying to prisoners except where courts order otherwise. With the Supreme Court primed this term to rein in the Chevron deference doctrine – the judicial rule that courts defer to federal agencies’ interpretation of the statutes they administer – the BOP’s denial of FSA credits until an inmate reaches his or her assigned institution is an excellent case of how even Chevron can ban some BOP overreaching.

The FSA provides that a prisoner “who successfully completes evidence-based recidivism reduction programming or productive activities, shall earn time credits” according to a set schedule. Under 18 USC 3632(d)(4)(B), otherwise-eligible prisoners cannot earn FSA credits during official detention before the prisoner’s sentence commences under 18 USC 3585(a).” Section 3585(a) says a “term of imprisonment commences on the date the prisoner is received in custody awaiting transportation to, or arrives voluntarily to commence service of sentence at, the official detention facility at which the sentence is to be served.”

But the BOP puts its own gloss on the statute, directing in 28 CFR 523.42(a) that “an eligible inmate begins earning FSA Time Credits after the inmate’s term of imprisonment commences (the date the inmate arrives or voluntarily surrenders at the designated Bureau facility where the sentence will be served).”

Any prisoner who has spent weeks or months between sentencing and final delivery to his or her designated institution can see that the BOP rule can create months of FSA credit dead time.

Ash Patel filed a petition for habeas corpus seeking FSA credit from his sentencing in September 2020 until he finally reached his designated institution on the other side of the country in April 2023. The BOP argued his FSA credits only started in April 2023, stripping him of 2.5 years of earnings. The agency cited 28 CFR 523.42(a) and urged the Court to apply Chevron deference, accepting its interpretation of when FSA credits start.

The Court didn’t buy it. “Because Section 523.42(a) sets a timeline that conflicts with an unambiguous statute, it is not entitled to Chevron deference and the Court must give effect to the statutory text,” the judge wrote, citing Huihui v. Derr where the court held that while the prisoner was not eligible “before her sentence commenced, [] under 18 USC 3632(d)(4)(B)(ii), her ineligibility ended the moment she was sentenced… because FDC had already received her in custody.”

The Court didn’t buy it. “Because Section 523.42(a) sets a timeline that conflicts with an unambiguous statute, it is not entitled to Chevron deference and the Court must give effect to the statutory text,” the judge wrote, citing Huihui v. Derr where the court held that while the prisoner was not eligible “before her sentence commenced, [] under 18 USC 3632(d)(4)(B)(ii), her ineligibility ended the moment she was sentenced… because FDC had already received her in custody.”

Pavlo cites Yufenyuy v. Warden FCI Berlin, perhaps the first decision to refuse to give Chevron deference to the BOP’s incorrect 28 CFR 523.42(a) rule. He rightly complains that perhaps thousands of other prisoners ‘who were sentenced and have months of time in transit getting to their final designated facility… are currently not getting those credits.” Pavlo notes that “prisoners who have a disagreement with the BOP have access to an administrative remedy process to air their grievances. However, those in the chain of command at the BOP who would review those grievances have no authority within the BOP to award these credits as it deviates from the BOP’s own Program Statement, which remains unchanged… Currently, the only solution is for every prisoner who has this situation is to exhaust the administrative remedy process, something that could take 6-9 months, and go to court to find a judge who agrees with [Yufenyuy], which could take months more.”

Not necessarily. The Huihui v. Derr Court excused exhaustion because “further pursuit would be a futile gesture because… there is an error in [the BOPs] understanding of when Petitioner can begin earning credits under 18 USC 3632(d)(4)(B) and 3632(a)… The Court thus concludes that any further administrative review would not preclude the need for judicial review. The Court thus excuses Petitioner’s failure to exhaust her administrative remedies.”

Not necessarily. The Huihui v. Derr Court excused exhaustion because “further pursuit would be a futile gesture because… there is an error in [the BOPs] understanding of when Petitioner can begin earning credits under 18 USC 3632(d)(4)(B) and 3632(a)… The Court thus concludes that any further administrative review would not preclude the need for judicial review. The Court thus excuses Petitioner’s failure to exhaust her administrative remedies.”

Forbes, Bureau of Prisons’ Dilemma On First Step Act Credits (October 27, 2023)

Patel v. Barron, Case No C23-937, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 174601 (WD Wash., September 28, 2023)

Huihui v. Derr, Case No 22-00541, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 106532 (D. Hawaii, June 20, 2023)

Yufenyuy v. Warden FCI Berlin, No. 22-CV-443, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 40186 (D.NH, March7, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root